DC District Court Bats Down Northern Long-Eared Bat Listing

On January 28, 2020, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia released an opinion rejecting the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (the “Service”) 2015 decision to list the northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis) (the “Bat”) as “threatened” rather than “endangered” under the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”). [1] The Bat has been beset by a fast-spreading fungal infection known as white-nose syndrome, which has greatly reduced its numbers across much of its range. In 2015, the Service listed the Bat as “threatened” but did not list it as “endangered.” Shortly after that decision was made, the Center for Biological Diversity challenged it, claiming the Service’s decision violated the ESA. The court’s January 28 decision resolves that challenge. In its ruling, the court largely sided with the challengers and ordered the Service to revisit its listing determination. If the ruling is not appealed, the next step is for the Service to reconsider its listing decision and either maintain the status quo for the Bat as threatened or list the species as endangered. [2]

The Bat has figured prominently in the environmental reviews of a number of infrastructure projects across the United States, in light of the species’ wide-ranging territory. As a result, infrastructure advocates have sought to limit the Service’s approach toward the bat in order to ease permitting. For infrastructure developers, the January 28 decision and the ensuing agency actions could have a significant effect on project development going forward. We would expect the Trump Administration’s Service to seek to appeal the decision, or alternatively adjust the listing decision, in accordance with the Court’s guidance and re-issue a “threatened” determination with the Bat.

I. The Court’s Analysis

The Court’s ruling turns on three conclusions: (1) the Service improperly relied on a policy that said it did not need to consider whether the species was endangered, (2) the Service failed to consider cumulative effects in making a listing determination, and (3) the Service’s notice and comment procedures were flawed.

As background, the “Act defines an endangered species as any species that is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range and a threatened species as any species that is likely to become endangered throughout all or a significant portion of its range within the foreseeable future.” [3] In simple terms, an endangered species is on the brink of extinction now; a threatened species is likely to be on the brink in the future. Endangered species receive the cornerstone protections of the ESA, including a prohibition against any "take," which includes harming, harassing, collecting, or killing, under Section 9 of the ESA, unless authorized by an Incidental Take Permit. Threatened species do not automatically receive those protections under current policy, and the Service often creates exemptions to take prohibitions through use of a “Section 4(d) Rule.” In its 2015 listing decision, the Service used a multi-factor approach to conclude that, in aggregate, the Bat was threatened. Then, per Service policy, the agency concluded that it did not need to consider whether the Bat was also endangered. [4]

The Court rejected the Service’s analysis. First, the Court disagreed with the factors the Service relied on. The Service claimed one of the pivotal factors in its analysis revealed, “in the area not yet affected by [white-nosed syndrome (“WNS”)] (about 40 percent of the species’ total geographic range), the species has not yet suffered declines and appears stable.” [5] The Court disagreed, determining that the Service’s rationale was not supported by the best available scientific data. Rather, the Court found that the Bat is uncommon to rare on the outskirts of its range. FWS failed to provide a necessary rational explanation as to:

[W]hy the significant disparity in population density between the 60 percent of the range that is WNS-infected and the 40 percent that is not supports a threatened rather than endangered determination. Such an explanation is necessary in view of the significant population disparities between the WNS-infected areas and those areas not yet infected; the evidence that WNS is responsible for ‘unprecedented mortality’ and ‘has spread rapidly,’ resulting in population declines of the Bat of 96 to 99%, and that there are ‘no known examples of Bats that have survived’ a WNS infection… [fails] to articulate a rational connection between the facts found and the choice made. [6]

Accordingly, the Service’s analysis was insufficient to warrant a threatened listing.

Second, the Court found that the Service failed to consider the cumulative effects of potential threats. [7] The ESA requires a listing agency to consider a series of factors both individually and cumulatively to determine if a species is threatened or endangered. [8] The Court concluded that even though the Service considered the impact of WNS on the Bat, the agency failed to account for other natural and manmade factors that may have a cumulative effect on the species. As a result, the Court held that the FWS listing of the bat was arbitrary and capricious. [9]

Third, the Court held that the Service violated the ESA by declining to conduct an endangered species analysis after determining the Bat was threatened throughout its range. According to the agency’s existing “Final Significant Portion of Its Range” policy (the “Final SPR Policy”), the Service is not required to consider whether the Bat was endangered in a significant portion of its range if it makes a determination that a species is threatened throughout all of its range. [10] However, the Court determined that (1) the standard for listing in the ESA is unambiguous, and (2) even if the standard was ambiguous, the Final SPR Policy misinterprets the ESA. [11] The Court held that “Congress’ intent in enacting the ESA and creating two levels of classification was to provide incremental protection to species in varying degrees of danger.” [12] The Court determined that failing to consider both threatened and endangered status is an unreasonable interpretation of the ESA. [13] In reaching this conclusion, the Court invalidated the Final SPR Policy claiming it is unlawful and therefore cannot be applied to support listing classifications by the FWS.

Procedurally, the Court remanded the Service’s listing decision without vacating its threatened listing. That means the Bat is still listed as threatened and will remain that way at least until the Service issues a new listing decision. Going forward, the court’s ruling suggests that the Service may no longer halt its analysis once it determines that a species is threatened throughout all of its range; it must continue and ascertain whether the species is endangered in a significant portion of its range as well. It remains to be seen what the outcome will be for the Bat.

II. Impact of “Up-listing” the Northern Long-Eared Bat

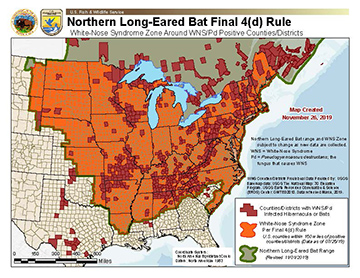

If the Service were to list the Bat as endangered, several important results would follow. The full take prohibition would automatically apply, eliminating the exemptions that are currently in the 4(d) rule. [14] Under the 4(d) rule, there was no prohibition on incidental take of the Bat outside of the WNS zone. [15] An up-listing would eliminate that exemption. Any take on a Bat habitat would require an Incidental Take Permit and a Habitat Conservation Plan pursuant to § 10 of the ESA. The automatic prohibition on take could result in major barriers to wind projects, building construction, pipelines, or any construction that may require tree clearing in large portion of the United States. [16] Further, an endangered classification carries greater penalties for violations of a species compared to those listed as threatened. [17]

To download full map, click here.

III. Conclusion

The final impact of the Court’s decision remains undetermined. In light of the Trump Administration’s strong support for infrastructure investment and construction, we expect the Service will look for ways to limit the impacts of the court’s decision on such development. In fact, the Court’s opinion may create major policy shifts in how the ESA is implemented by listing agencies. At this time, there is no indication whether the Plaintiffs or the Service will appeal the Court’s decision.

Notes

[1] Center for Biological Diversity v. Everson, No. 15-CV-477, 2020 WL 437289 (D.D.C. Jan. 28, 2020) (hereinafter “Everson”).

[2] Id.

[3] Everson at *4-5. FWS concluded that the Bat was a threatened species because, “[1] WNS has not yet been detected throughout the entire range of the species, and will not likely affect the entire range for ... most likely 8 to 13 years. [2] In the area not yet affected by WNS (about 40 percent of the species’ total geographic range), the species has not yet suffered declines and appears stable. [3] The species still persists in some areas impacted by WNS, thus creating at least some uncertainty as to the timing of the extinction risk posed by WNS. Even in New York, where WNS was first detected in 2007, small numbers of Bats persist ... despite the passage of approximately 8 years. [4] Coarse population estimates where they exist for this species indicate a population of potentially several million Bats still on the landscape across the range of the species.”

[4] Id. at *5 (citing Final Policy on Interpretation of the Phrase “Significant Portion of Its Range” in the Endangered Species Act’s Definitions of “Endangered Species” and “Threatened Species,” 79 FR 37,577 (July 1, 2014) (“Final SPR Policy”); FWS also claimed that listing the Bat as both endangered and threatened would lead to confusion. Id. at *20.

[5] Id. at *5.

[6] Id. at *8.

[7] Cumulative effects review is required under § 7 of the ESA. This review is separate from a National Environmental Policy Act cumulative effects review that Trump administration looks to eliminate in its Update to the Regulations for Implementing the Procedural Provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act. See 85 Fed. Reg. 1684 (Jan. 10, 2020).

[8] “(A) the present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of a species’ habitat or range; (B) overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes; (C) disease or predation; (D) the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; and (E) other natural or manmade factors affecting a species’ continued existence.” 16 U.S.C § 1533(a)(1)(A)-(E); see also 50 C.F.R. § 424.11(c).

[9] Everson at *10.

[10] Final SPR Policy, 79 Fed. Reg. 37,577 (July 1, 2014).

[11] Id. at *17-18.

[12] Id. at *19 (citing Defenders of Wildlife v. Norton, 258 F.3d 1136, 1143 (9th Cir. 2001)).

[13] Id. at *20.

[14] J.B. RUHL ET AL., THE PRACTICE AND POLICY OF ENVIRONMENTAL LAW 78 (4th ed. 2017).

[15] FWS created a two-region approach: areas within the range of the Bat where WNS has not been identified and areas within the WNS zone, counties within 150 miles of positive identification of WNS infection. The Rule also provided that “activities not involving tree removal were not prohibited, provided they do not result in the incidental take of the Bat in hibernacula or otherwise impair essential behavioral patterns at known hibernacula.” Ankur Tohan & James Lynch, The Final Northern Long-Eared Bat 4(d) Rule: Impacts to Energy Infrastructure Projects, K&L GATES (Jan. 2016), http://www.klgates.com/files/Publication/eb6e73a7-3fc3-4b1d-8261-74baf5f849f4/Presentation/PublicationAttachment/19ae8c84-d6fe-4b2e-b293-b84be7c42188/ELNR_Alert_01192016.pdf., at 3-4.

[16] See Barry Hartman et al., Bats in the Balance: Northern Long-Eared Bat Listing and Interim 4(d) Rule, K & L GATES (May 2015), http://www.klgates.com/files/Publication/dc16f333-647d-46b4-88a3-b42b0ff90592/Presentation/PublicationAttachment/b15a71a8-4bdd-4118-948b-c0ce53dc75c5/ELNR_Alert_0562015.pdf.

[17] RUHL, supra note 25, at 78.

This publication/newsletter is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer. Any views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the law firm's clients.