Greater Sage-Grouse and Land Use in the Inter-Mountain West

Introduction

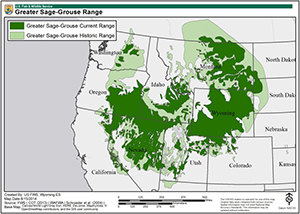

The greater sage-grouse—a ground-dwelling, chicken-like bird—has been the focus of controversy pitting conservation against energy development and ranching interests across the inter-mountain west. The greater sage-grouse’s habitat covers 165 million acres in eleven western states. This fall, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (“FWS”) is expected to decide whether to list the greater sage-grouse under the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”). The FWS’ decision is due by September 30, 2015. If listed, actions on federal lands would require ESA consultation and actions on wholly private lands may require an ESA incidental take permit, if take cannot be avoided.

Against a backdrop of controversy involving the status and protection of the greater sage-grouse, the FWS and a variety of stakeholders are taking creative steps that may help avoid listing the species as endangered or threatened under the ESA. In late May, the Bureau of Land Management (“BLM”) and the U.S. Forest Service (“USFS”) announced a joint effort to conserve the greater sage-grouse on federal lands in ten western states. This represents the latest in a series of public and private efforts to head off an ESA listing.

Congress, aware of the impact a listing could have on western lands, has also moved to avoid it. A current budget proviso bans writing or issuing a final rule in 2015, and there is a proposal to extend the ban through the end of 2016. [1] Pending House and Senate bills also propose a 10-year bar on listing. [2]

The BLM and USFS greater sage-grouse conservation plans limit energy development on federal land: large-scale wind and solar projects are directed away from certain greater sage-grouse habitat areas, transmission lines for large-scale wind and solar may not be located in sage-grouse habitat, and no-surface occupancy measures [3] are required for some new federal oil and gas leases. But an ESA listing of the greater sage-grouse could impose even more significant restrictions that may impact land use on 165 million acres of private, state and federal lands. The BLM, USFS plans could help prevent an ESA listing and keep the inter-mountain west open to responsible development.

The Saga of the Greater Sage-Grouse and the ESA

The greater sage-grouse has been the subject of ESA debate and litigation for 15 years. Its population, once estimated to be in the millions, now hovers around 200,000 to 500,000. Its habitat covers 165 million acres across eleven western states, a loss of 56 percent from its historic range. Of the 165 million-acre range, 64 percent is located on federal land, 31 percent on private land, and 5 percent on state land. Wyoming has the largest population with 37 percent of the total. Montana has 18 percent, Nevada and Idaho both have 14 percent, and the remaining states each have less than 7 percent. [4]

Map source: http://www.fws.gov/greatersagegrouse/maps/20140815_GRSG_Range.jpg

In 2010, the FWS determined that listing the greater sage-grouse under the ESA was warranted, but precluded by other higher priority species. [5] Factors supporting listing included the continued fragmentation and degradation of the greater sage-grouse habitat, and inadequate existing local, state, and federal regulations. Specific habitat threats included agriculture, urbanization, infrastructure (such as roads and power lines), wildfires, invasive plants, grazing, climate change, and energy development. The FWS concluded that the existing local, state, and federal regulatory mechanisms were inadequate to protect the species and that in particular existing regulatory mechanisms on BLM and USFS lands were insufficient. [6] Since 64 percent of greater sage-grouse habitat is on federal lands, the lack of regulatory mechanisms there posed a significant threat.

Environmental groups sued FWS for the 2010 “warranted but precluded” listing determination. In 2011, the FWS reached a sweeping settlement with environmental groups requiring the agency to issue listing decisions for hundreds of candidate species on a specific timeline. In particular, the FWS must issue a listing decision for the greater sage-grouse, including any Distinct Population Segments (“DPS”), [7] by September 30, 2015. [8] Despite the provision in the FY 2015 omnibus appropriations bill barring Interior from using any funds to issue or write a greater sage-grouse ESA rulemaking, FWS does not believe that the rider has any effect “on ongoing efforts to develop and implement federal and state plans that conserve sagebrush habitat or to completing the requisite analysis for potential rulemaking.” [9] Thus, the agency is still expected to reach a decision by the September 30 deadline.

In April 2015, the FWS recently withdrew its proposed rule to list the Bi-State (applicable to Nevada and California) DPS of the greater sage-grouse as threatened, [10] citing successful conservation efforts and the implementation of the Bi-State Action Plan. This could signal that FWS will issue a “not warranted” determination of the greater sage-grouse this fall. The Bi-State Action plan is a collaborative conservation plan developed between federal, state, and local agencies and landowners in Nevada and California with $45 million in funding to implement conservation efforts over the next ten years. [11] Interior Secretary Sally Jewell recently told the Western Governor’s Association that the withdrawal of the proposed rule for the Bi-State sage grouse indicates that a “not-warranted listing is a clear possibility” for the greater sage-grouse if states and the federal government continue to work together. [12]

The Implications of a Greater Sage-Grouse Listing Under the ESA

Given that the greater sage-grouse’s habitat spans 165 acres in 11 states, an ESA listing could have a significant impact on land uses in the west. Section 9 of the ESA protects listed species from a “take” (e.g., action that would harass, harm, capture, or kill). [13] Listing the bird as endangered would mean that no one could “take” a greater sage-grouse on public or private land unless they first secure an incidental take permit, which is a time-consuming and expensive process. [14]

If the species is listed as threatened, FWS may issue regulations “necessary and advisable to provide for the conservation of such species.” [15] A listing as threatened can be accompanied by a 4(d) rule, which can relax ESA restrictions to minimize conflicts between threatened species and people. For instance, the FWS recently listed the northern long-eared bat as threatened and issued an interim 4(d) rule that exempted certain land use activities from the incidental take prohibition. [16] If the greater sage-grouse is listed as threatened, the FWS could exempt specific activities from take prohibitions, such as wind energy production and oil/gas drilling.

The BLM, USFS Greater Sage-Grouse Conservation Effort

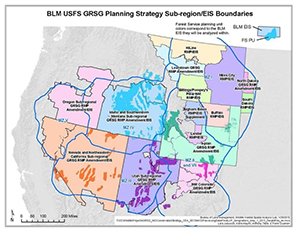

In an effort to demonstrate that a listing of the greater sage-grouse is not warranted, the BLM and USFS recently released a series of revised land-use plans to conserve the greater sage-grouse on federal lands in ten western states (CA, CO, ID, MT, NV, ND, OR, SD, UT, WY). [17] BLM officials call the conservation effort “the single largest public land planning effort in United States history.” [18]

Nearly two-thirds of the greater sage-grouse’s habitat is on federal lands, so the BLM, USFS greater sage-grouse conservation strategy is essential to the survival of the species and could help prevent an ESA listing this fall. The land use plans are a direct response to the 2010 FWS conclusion that existing regulatory mechanisms on BLM and USFS land were inadequate to protect the greater sage-grouse. [19] In addition, the BLM, USFS effort signals to the FWS that, unlike in 2010, adequate regulations are now in place on federal land to preserve the greater sage-grouse and that listing the species as endangered or threatened under the ESA may not be warranted.

In the Final Environmental Impact Statements (“FEIS”) for the land-use plans (the “plans”), the agencies selected an approach that sought to balance competing human needs and interests with the protection, restoration, and enhancement of the greater sage-grouse habitat. BLM and USFS worked closely with FWS, the United States Department of Agriculture (“USDA”) Natural Resources Conservation Service (“NRCS”), western states, and other stakeholders for more than two years to develop these plans. The plans will be finalized later this summer after a 60-day Governor’s Consistency Review and a concurrent 30-day protest period. [20]

The plans have three objectives: minimize surface disturbance of sage-grouse habitat, improve habitat condition, and reduce the threat of rangeland fire to sage-grouse and sagebrush habitat. [21] To achieve those objectives, the plans designate three levels of sage-brush habitat, and within each habitat area various land use activities are prohibited, restricted, or permissible. First: “General Habitat Management Areas” (“GHMAs”), which are the most flexible and permissible habitat areas for land use activities. Second: “Priority Habitat Management Areas” (“PHMAs”), which have the highest conservation value for maintaining sustainable greater sage-grouse populations. Third: “Sagebrush Focal Areas” (“SFAs”), which are a subset of PHMAs and are considered “strongholds” for the species. They include the highest breeding population densities and existing high-quality sagebrush habitat. Land use activities are most restricted within SFAs. [22] [23]

To minimize surface disturbance of greater sage-grouse habitat, the plans limit certain land use activities and energy development. The plans impose a disturbance cap in PHMAs to prevent further surface disturbances (e.g., roads, oil and gas wells, buildings) and to prevent further habitat fragmentation. The plans identify minimum buffer areas around greater sage-grouse leks—sites where greater sage-grouse return every year to mate. The buffer distances vary by greater sage-grouse population and habitat.

The plans limits wind and solar energy projects on federal land. They steer large-scale wind and solar projects away from PHMAs, but allow such projects in GHMAs. Developers are also required to avoid placing transmission lines of large-scale wind and solar projects in sage-grouse habitat. If the sage-grouse habitat cannot be avoided, the plans require mitigation measures.

The plans also limit oil, gas, and mining on public lands. The plans prioritize new leases and development of oil, gas, and geothermal projects outside of PHMAs and GHMAs and limit surface disturbances from new federal leases in PHMAs and SFAs. To limit surface disturbances and protect sensitive sage-grouse habitats, states that lack an all-lands regulatory approach to managing disturbance are required to adopt no-surface-occupancy measures in new federal oil and gas leases in SFAs, and, with exceptions, in PHMAs. BLM will still recognize all valid, existing oil, gas, and geothermal projects. According to BLM and USFS, 90 percent of lands with high to medium potential are located outside of PHMAs. To minimize surface disturbances from mining, the plans ensure that the sage-grouse habitat is considered when BLM reviews proposed coal mines or coal mine expansions. The plans also recommend that the Secretary of the Interior use her authority to withdraw hardrock mining from SFAs.

Private lands conservation efforts to avoid an ESA listing

While the BLM, USFS conservation effort helps to conserve the greater sage-grouse on federal land, conservation efforts on private lands are also underway. Eighty percent of essential summer habitat where sage grouse raise their young (i.e., in wet habitats) are located on private lands. [24] Fortunately, many western states have already taken steps to conserve the greater sage-grouse on private property. These efforts help ensure that sufficient protections are in place to conserve the greater sage-grouse and could help avoid an endangered or threatened listing this fall.

Many states have taken steps to conserve the greater sage-grouse on state and privately owned land. For instance, in March 2015, Wyoming and FWS launched the nation’s first greater sage-grouse conservation bank. The conservation bank enables development entities to purchase credits to offset impacts to the greater sage-grouse occurring elsewhere. [25] In May 2015, Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper issued an executive order to protect the greater sage-grouse throughout the state. The executive order contained multiple components, such as instructing the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission to foster mitigation and conservation efforts and creating a market-based habitat exchange. [26] In 2014, Montana Governor Steve Bullock created the Sage Grouse Habitat Conservation Program, which established a variety of limitations and stipulations to conserve the species within the state. [27]

Wyoming and Oregon have greater sage-grouse Candidate Conservation Agreements (“CCAs”) and Candidate Conservation Agreement Assurances (“CCAAs”) in effect. [28] In 2013, Wyoming finalized an umbrella CCAA with FWS to establish a greater sage-grouse conservation framework for livestock grazing and ranch management on private and state land. [29] The umbrella CCAA encompasses more than 17 million acres of privately owned land. As of January 2015, more than 300,000 acres are enrolled in Wyoming’s umbrella CCAA, and nearly 50,000 acres of greater-sage grouse habitat are enrolled in CCAs. If participating landowners create a site-specific conservation plan that is consistent with the umbrella CCAA, the FWS will issue the landowner an Enhancement of Survival permit. The permit is valid for twenty years. Oregon has three CCAAs throughout the state. More than 4 million acres of privately owned land now qualify for CCAAs to conserve the greater sage-grouse. [30] If Congress continues to pass legislation that prohibits FWS from issuing a listing of the greater sage-grouse, private property owners may find the time and expense of crafting a CCAA with FWS worthwhile.

Private and non-profit entities are also taking action to conserve the greater sage-grouse and prevent the species from being listed under the ESA. In 2010, USDA’s NRCS formed the Sage Grouse Initiative (“SGI”) after the FWS listed the bird as a candidate species. The SGI partnership includes ranchers; local, state, and federal agencies; non-profit groups; and business. SGI focuses mostly on reducing threats to the greater sage-grouse on private lands. Since SGI began in 2010, the organization has invested $425.5 million in greater sage-grouse conservation efforts, working with 1,129 ranches to restore more than 4.4 million acres of the species’ habitat. [31]

Conclusion

An endangered or threatened listing of the greater sage-grouse would limit land use activities throughout 165 million acres in the western U.S. Local, state, and federal agencies, private landowners, and nonprofits have gone to great lengths to conserve the species and avoid an ESA listing. Those collective efforts impact land-use activities and will have long-term implications for energy development across the inter-mountain west. It remains to be seen whether these efforts will be enough for the FWS to issue a “not warranted” determination this fall.

Notes:

[1] A provision in the Fiscal Year 2015 (“FY 2015”) omnibus appropriations bill prohibits the Department of Interior (“Interior”) from using any FY 2015 funds to write or issue a proposed rule for the greater sage-grouse. See Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act of 2015, Pub. L. No. 113-235, 128 Stat. 2421. The House Appropriations Committee FY 2016 Interior and Environment appropriations bill would extend the delay for another year. Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2016, H.R. 2822, 114th Cong. Sec. 117 (as introduced June 18, 2015).

[2] Congressional efforts to prevent a greater sage-grouse listing extend beyond appropriations bills: the House version of the 2016 National Defense Authorization Act (“NDAA”) includes a provision that would delay a greater sage-grouse listing for ten years. See National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016, H.R. 1735, 114th Cong. § 2862 (as passed by House, May 15, 2015). Senator Mike Lee (R-UT) introduced a similar amendment to the Senate NDAA bill that would delay a greater sage-grouse listing for ten years and also limit the implementation of the USFS, BLM Greater-Sage Grouse Conservation Effort. S. Amdt. 1687, 114th Cong., (amendment proposed June 11, 2015).

[3] No surface occupancy means lease stipulations that prohibits occupancy or disturbance on all or part of the lease surface to protect special values or uses. Lessees may develop the oil and gas or geothermal resources under leases restricted by this stipulation through use of directional drilling from sites outside the no surface occupancy area.

[4] See U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., The Greater Sage-Grouse: Facts, Figures, and Discussion (last visited June 26, 2015) http://www.fws.gov/greatersagegrouse/factsheets/GreaterSageGrouseCanon_FINAL.pdf.

[5] Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 12-month Findings for Petitions to List the Greater Sage-Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus),75 Fed. Reg. 13910-14014. To determine whether a species is endangered or threatened, the FWS considers five factors. See 16 U.S.C. § 1533(a)(1)(A-E).

[6] Id. at 13982.

[7] “Distinct Population Segment” (“DPS”) is the smallest subset of a species that can be listed under the ESA. DPSs are limited to vertebrates. See 15 U.S.C. § 1532(16).

[8] Mining and ranching interests in Nevada filed suit in late 2014 challenging the validity of the 2011 Settlement Agreement, specifically alleging that the September 30, 2015 greater sage-grouse deadline violates the ESA, the Administrative Procedure Act, and the U.S. Constitution. The case has now been transferred to the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. See F.I.M. et al. v. U.S. Department of the Interior, No. 1:15-cv-00897-EGS (D.D.C. filed June 9, 2015).

[9] Press Statement, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Statement by Interior Secretary Sally Jewell on the Sage-Grouse Rider in the FY15 Omnibus Bill (Dec. 17, 2015), http://www.fws.gov/news/ShowNews.cfm?ID=59D5150F-A05D-A1AD-9E69AE3066E2183E.

[10] Withdrawal of the Proposed Rule To List the Bi-State Distinct Population Segment of Greater Sage-Grouse and Designate Critical Habitat, 80 Fed. Reg. 22827 (Apr. 23, 2015).

[11] See Press Release, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Successful Conservation Partnership Keeps Bi-State Sage-Grouse Off Endangered Species List (April 21, 2015), http://www.fws.gov/news/ShowNews.cfm?ID=DD5B828A-EFD6-2D90-B779A121E74DD059.

[12] Jeff DeLong, Sage Grouse Could Evade Endangered Status, Reno Gazette-Journal (June 24, 2015), http://www.rgj.com/story/news/2015/06/24/sage-grouse-evade-endangered-status/29246867/.

[13] 16 U.S.C. § 1538.

[14] 16 U.S.C. § 1539.

[15] 16 U.S.C. § 1533(d).

[16] See Barry M. Hartman, et. al., Bats in the Balance: Northern Long-Eared Bat Listing and Interim 4(d) Rule, K&L Gates (May 6, 2015), http://www.klgates.com/bats-in-the-balance-northern-long-eared-bat-listing-and-interim-4d-rule-05-06-2015.

[17] The BLM, USFS land use plans and FEIS’ are available at http://www.blm.gov/wo/st/en/prog/more/sagegrouse.html (last visited June 25, 2015). Washington was not included since Washington’s greater sage-grouse population is predominantly located on private land.

[18] Marianne Lavelle, Sage grouse war tests limits of partnership in West, Science Magazine News (June 19, 2015), http://news.sciencemag.org/plants-animals/2015/06/feature-sage-grouse-war-tests-limits-partnership-west.

[19] Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 12-month Findings for Petitions to List the Greater Sage-Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus),75 Fed. Reg. 13982.8. The Federal Land Policy and Management Act and National Forest Management Act direct BLM and the USFS to periodically update the plans, which guide all actions and approved uses on public land.

[20] See 43 CFR §§ 1610.3-2(e), 1610.5-2 (2015). Protests have been filed by conservation and industry groups, and Governor Mead of Wyoming. See, Benjamin Storrow, Industry and environmentalists share dislike for federal sage grouse plan, Casper Star Tribune (July 6, 2015), http://trib.com/business/energy/industry-and-environmentalists-share-dislike-for-federal-sage-grouse-plan/article_f1b8c4b3-be25-5e11-ab0d-1f44e44ea7b0.html.

[21] For more information on the land use plans, see Bureau of Land Management, Fact Sheet: BLM, USFS, Greater Sage-Grouse Conservation Effort (last visited June 25, 2016), http://www.blm.gov/style/medialib/blm/wo/Communications_Directorate/public_affairs/sage-grouse_planning/documents.Par.93163.File.dat/BLM-USFS%20Plans%20Fact%20Sheet%20Final.pdf.

[22] As to the relative size of these designated areas, GHMAs are the usually the largest habitat management area within a planning area, PHMAs are the second-largest, and SFAs are the smallest. Within the Wyoming greater sage-grouse planning area, for example, 4,894,900 acres were identified as PHMAs (about 30 percent of the planning area), 1,196,000 acres were identified as SFAs, and 5,951,300 acres were identified as GHMAs (37 percent of the total planning area). Bureau of Land Management, Wyoming Greater Sage-Grouse Proposed LUP/FEIS: Executive Summary, ES-4, ES-6 (May 28, 2015), https://eplanning.blm.gov/epl-front-office/projects/lup/9153/58379/63908/05_Executive_Summary.pdf.

[23] For a map of the GHMAs, PHMAs, and SFAs in Montana’s HiLine District, see Bureau of Land Management, Map 2.18 Greater Sage-Grouse & Grassland Bird Habitat Management Areas Alternative E (Preferred) (last visited July 22, 2015), Maps of other habitat management areas for the plans are available within the BLM, USFS FEIS’, available at http://www.blm.gov/wo/st/en/prog/more/sagegrouse.html (last visited June 25, 2015).

[24] Sage Grouse Initiative, Science to Solutions: Private Lands Vital to Conserving Wet Areas (2014), http://www.sagegrouseinitiative.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Science-to-Solutions-Conserving-Wet-Areas-FINAL-LOW-RES-091614.pdf.

[25] See Press Release, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., State of Wyoming, Sweetwater River Conservancy Launch Nation’s First Greater Sage-Grouse Conservation Bank (March 18, 2015).

[26] Colo. Exec. Order D 2014-004, May 15, 2015, https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/atoms/files/EO-D-2015-002.pdf.

[27] Mont. Exec. Order No. 10-2014, Sept. 9, 2014, https://governor.mt.gov/Portals/16/docs/2014EOs/EO_10_2014_SageGrouse.pdf.

[28] CCAs and CCAAs are another way to conserve the greater sage-grouse on private property. Individual property owners may enter into voluntary agreements with the FWS to conserve the candidate species, so that an ESA listing may not be necessary. The FWS can enter into CCAs with states, local governments, tribes, and private property owners. CCAs however, unlike CCAAs, do not provide any permits that authorize incidental takes or assurances should the candidate species eventually be listed under the ESA. A CCAA provides property owners an Enhancement of Survival permit under Section 10 of the ESA. The permit provides assurances to the property owner that if the candidate species is eventually listed, they do not have to engage in additional conservation measures and they are entitled to a specific level of incidental take of the covered species without penalty. CCAs and CCAAs conserve candidate species on private property to help avoid an ESA listing and provide certainty to private property owners. States, tribes, and local governments may create programmatic or “umbrella” CCAAs with FWS and then enroll individual property owners in a specific region. See U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Candidate Conservation (last updated June 16, 2014), http://www.fws.gov/endangered/what-we-do/cca.html.

[29] See U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Greater Sage-Grouse CCAA for Wyoming Ranch Management (last visited June 26, 2015), http://www.fws.gov/wyominges/Pages/LandownerTools/CCAA/CCAA_GSG.html.

[30] See Press Release, USDA, Secretary Jewell, Governor Brown, Deputy Under Secretary Mills Celebrate Landmark Agreements to Conserve up to 2.3 Million Acres of Sagebrush Habitat in Oregon (March, 27, 2015), http://www.usda.gov/wps/portal/usda/usdamediafb?contentid=2015/03/0077.xml&printable=true&contentidonly=true.

[31] See USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Outcomes in Conservation: Sage Grouse Initiative (February 2015), http://www.sagegrouseinitiative.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/NRCS_SGI_Report.pdf.

This publication/newsletter is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer. Any views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the law firm's clients.