Litigation Minute: A Year After Loper Bright Part II: States Follow Suit

What You Need to Know in a Minute or Less

Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo shook the legal world when it overturned one of the cornerstones of administrative law: the Chevron doctrine. Established by Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., the Chevron doctrine directed federal courts to defer to an agency’s reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous statute that the agency administers.

In Part I of this series, we looked at how the federal courts have begun to implement Loper Bright one year after the seminal case; here, we dive into where things stand at the state level.

In a minute or less, here is what you need to know.

States Still Free to Go Their Own Ways

The Chevron doctrine was a rule about how courts should interpret federal law; state courts were never bound by it.1 In overturning Chevron, Loper Bright relied purely on statutory grounds under the Administrative Procedure Act. Because of this, state courts and state agencies are not bound by this decision either. However, many states tend to look to federal law and its trends as persuasive precedent for their own legal structures.

State of Play in the States

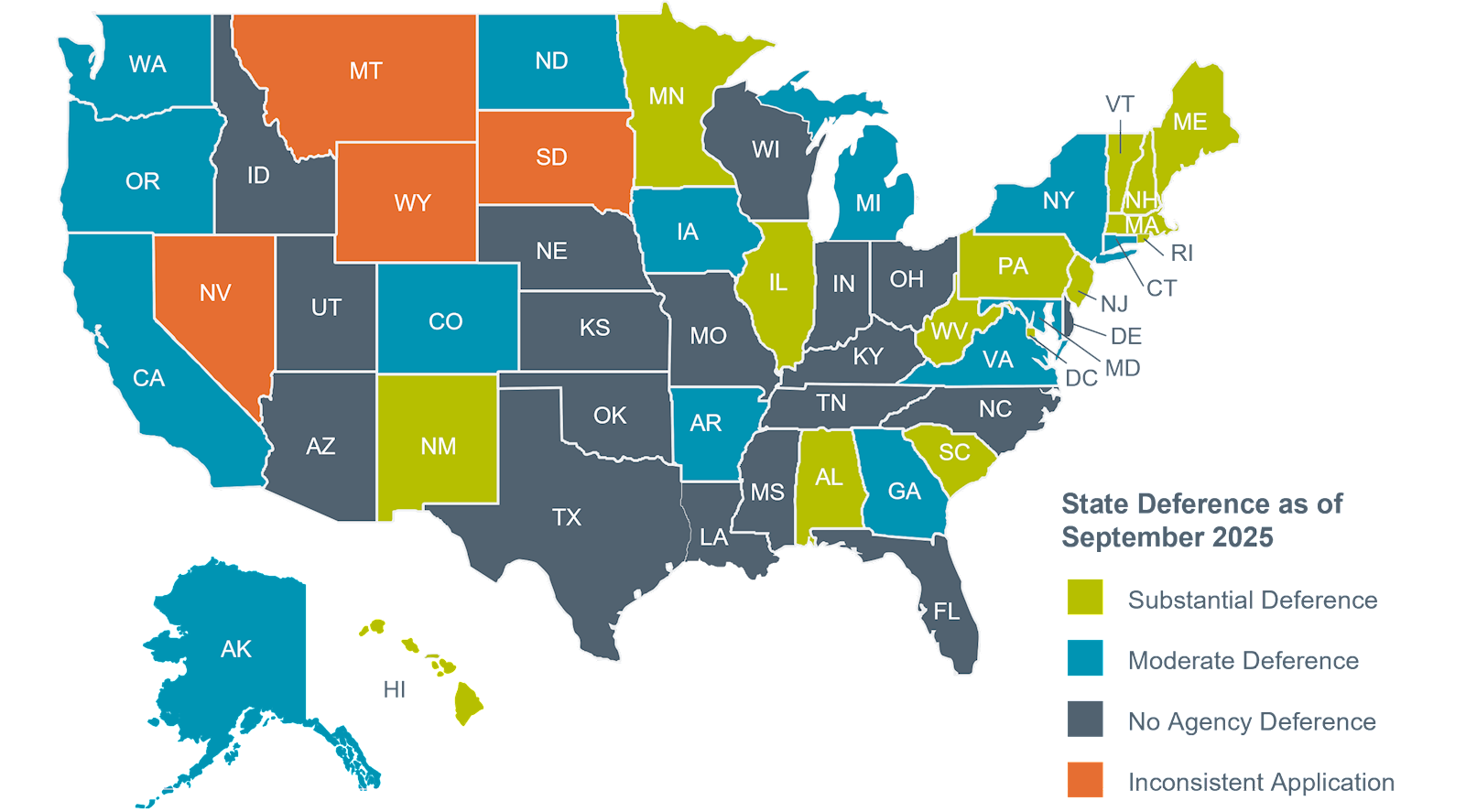

While at least 34 states give some level of deference to state agencies, there has been a recent trend limiting or eliminating such agency deference.2 In 2025 alone, North Carolina, Missouri, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah, and Kentucky have either ended or significantly limited deference to state agencies.

Generally, states are split into four general categories regarding deference practices:

- Fifteen states provide substantial deference to state agencies similar or stronger than Chevron. Examples include Illinois, D.C., and Massachusetts.3

- Fourteen states provide a moderate level of deference, although with great variety. Some states use a sliding scale to determine the weight of deference, others only providing deference to the interpretation of regulations but not statues, and some add additional tests that must be met in order for deference to attach. These standards vary and there are many unique tests for states that fall under this category. For example, Connecticut provides Chevron-like deference, but only if the agency’s interpretation has been previously subjected to judicial scrutiny or is “time tested.”4 In North Carolina, interpretations are treated as non-binding, with deference based on the ability of the agency to persuade the court. In Michigan, interpretations are given “due consideration,” but courts must provide “cogent reasons” for overturning.

- Four states appear inconsistent in their application of deference, with courts ruling both for deference and de novo review or declining to formally set rules of deference. Examples include Nevada and South Dakota.

- Eighteen states provide no deference.5

Despite Shift From Deference, States Remain Diverse

Even with seven states limiting deference this year, states that apply deference outnumber the states that don’t. And within the deference states, there still lies significant variation. Some states such as Illinois provide a “presumption of correctness” even in the absence of ambiguity, while others, such as Maryland, provide deference to regulatory interpretations based on a multi-factored sliding scale test. Virginia applies deference based on the ability of the agency to persuade the court based on reasoning and expertise.

The recent shift to abolish or limit deference is also not universal. The Hawai’ian Supreme Court rejected the reasoning set forth in Loper Bright, stating: “[n]ow, the U.S. Supreme Court considers itself and other federal courts the experts on exceedingly complicated areas of American Life…In Hawai‘i, we defer to those agencies with the na‘auao (knowledge/wisdom) on particular subject matters to get complex issues right.”6

The Takeaway

While the abandonment of the Chevron doctrine has led many states to end or restrict deference to state agencies, there still remains significant variation in state application. This trend is not likely to change anytime soon.

Our Administrative Law and Appellate Litigation practitioners regularly assist clients in assessing regulatory actions and legal risk in light of evolving judicial precedents.

This publication/newsletter is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer. Any views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the law firm's clients.